Hello friend, welcome to Scrap Facts. I’m Katherine, and I’m glad you’re here.

I went to see the band Franz Ferdinand this week. If you don’t know them, they were biggest in the early aughts—aka the height of my teens.

I had been looking forward to it for months. When tickets went on sale, I only bought one. Something told me that it’d be really nice to take myself on a date.

It was great—I highly recommend solo concert going at least once in your life. As I shouted along to songs old enough to legally drink, I found that despite my attempts to spend time alone, I had brought a plus one after all: my teenaged self.

Like most people, I cringe when I think of my adolescence. The fashion! The acne! The angst! I was both hypercritical and hyper-defensive about myself and others. I wanted attention, yet panicked when I got any. What I remember more than any single event of that time period was an intense longing that felt fundamental to me as a person. I was desperate to reach adulthood and independence, yet terrified of any situation that would require me to do something without the validation of at least five of my peers.

As I entered my 20s, often I scoffed at the idea of my teenaged self. What a self-centered idiot I thought as I obliviously knocked my backpack into fellow commuters on public transportation. (My 20s were also not my best years.)

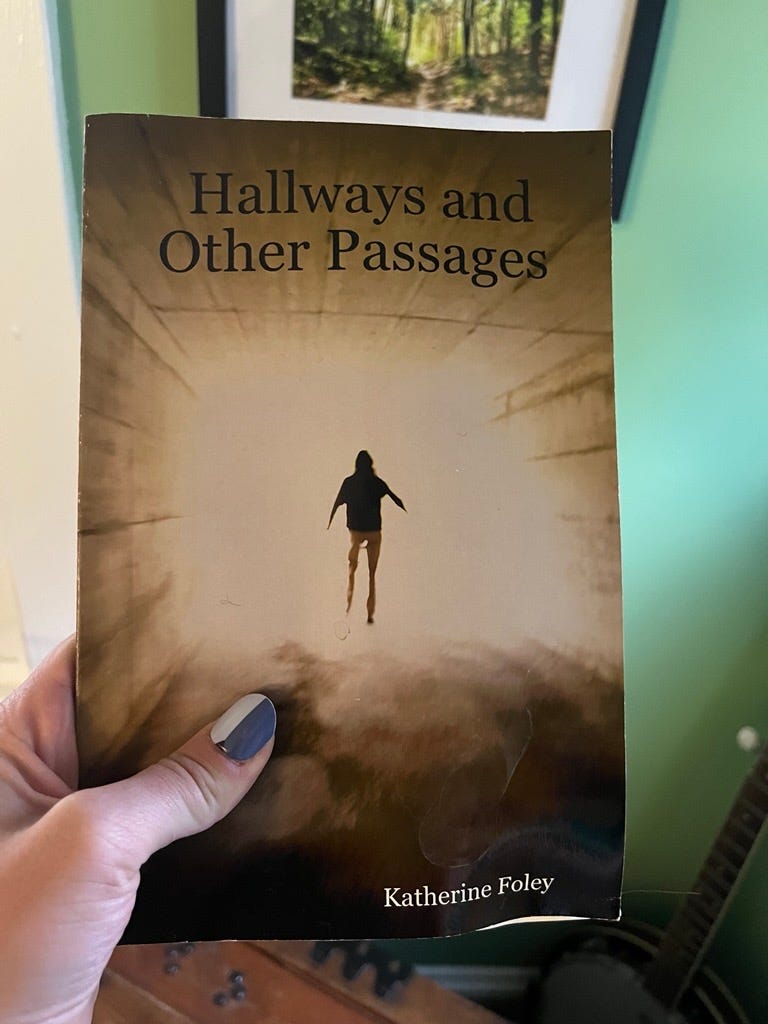

When I settled into my first permanent home, my parents bequeathed me all my relics from my childhood. They’re in a giant, rarely opened chest sitting in our living room, full of yearbooks and journals and even a collection of self-published short stories I wrote when I was 13 called—I kid you not—Hallways and Other Passages. These stories, with titles such as “Murdering Myself” and “Another Statistic,” are as good (truly, so bad) as they sound.

(To their credit, my parents were terribly proud of me for finishing it. I don’t remember them specifically commenting on the quality of the work, but they never failed to remind me that it showed I could start an ambitious creative project and finish it. I remain very grateful for their grace in that moment.)

I’m afraid to go through that chest because I am fairly certain it will cause me to be the first person to die of embarrassment. The only times I have gone through Hallways is in the company of deeply trusted friends when we need a good laugh. Even then, I feel too exposed after reading more than a page or so.

But I also can’t bear to get rid of what must be thousands of pages of writing by teenaged KEF. The idea of throwing these journals out makes me feel protective of something I can’t quite pinpoint. That chest would be there anyway, I tell myself. They’re not taking up space. So I leave them be.

At Franz Ferdinand, I sang my heart out and danced so hard I got sweaty. During a particularly juicy buildup to a song of my youth, I started laughing. Really laughing, almost manically. I doubled over and grabbed the bar in front of my section for support. For a second, I wondered if those near me were looking at me, and then I decided I didn’t care.

I had just realized that, at least in that moment, I had grown up to be the kind of person I’d idolized when I first heard the song decades ago. I was out on my own dime, looking fierce, and simply, blissfully present. My teenage self could both relax and rejoice.

It occurred to me on the drive home that I spent so much time trying to distance myself from my younger self—the awkward, stressed, painfully self-conscious person I was—I never thought to ask what she actually needed and why she was hurting so badly in the first place.

Some of the worst memories of my life are from my teenage years. Adults who were supposed to love me did things that were very wrong. Back then, I logically knew it was wrong, but I still felt like I deserved it. It was confirmation that my self-hatred was valid.

When I tell friends what happened, many don’t understand that I’ve forgiven the adults in question. I know I don’t owe it to them—but now that I’m closer to the age that they were at the time, I understand that these were just flawed people doing the best they could with not enough support. They have to live with themselves to this day—that can’t be easy.

In my forgiveness to them, though, I never bothered to go back and cherish my younger self. I just brushed her off as a kind of shitty, early draft of my present form. But if I’m honest, a lot of the things I hated about myself as a teenager came from just being really, really scared that something was wrong fundamentally with me—that I was too annoying, too much, and ultimately unlovable beyond a certain point. I worried that eventually, everyone I came to love would realize this and leave.

I wasn’t thinking about forgiving teen KEF, but I think that’s what ultimately happened. It felt really nice, seeing my worst years though loving eyes rather than judgmental ones. Plus, the show was really good. Even in their 50s, Franz Ferdinand knows what they’re doing. It’s a good reminder that peaking in life is a choice.

I originally intended to write this essay about forgiveness in general. To me, it’s a secret last stage of grief, just past acceptance—even if it isn’t always rational, like in the face a random death. Forgiveness brings the experience of loss or hurt back to love—or at least compassion for our fellow flawed neighbors.

I’ve been having a hard time, though, thinking through forgiveness in the the state of the world. Does everyone deserve forgiveness? Especially those making most of the headlines today? No. I don’t think they do. There are some people, most of whom I have never met, who I will never forgive.

When I look back on what happened when I was a teenager, I think the adults in my life must have been under similar external stressors themselves. It’s not an excuse, but it’s a reminder that we can’t choose our circumstances, but we can choose if we let them mold us into the worst versions of ourselves. We may not know better at the time, but we can learn.

I’m still working through a lot of forgiveness. It’s hard, because it requires working through all the other stages of grief first. Famously, none of these are pleasant. It takes a lot effort to feel my way through the emotions that come with acknowledging pain others caused me, pain I caused others, and pain I feel knowing I caused it for others. It sucks, but the alternative is carrying all that small-scale resentment for myself or others forever. It adds up.

Reader, I won’t pretend to know your life or your circumstances. But I would assume, given my modest following in this space, that you probably could practice more forgiveness in your life—at the very least for yourself. It’s not necessarily an easy journey, but it’ll probably take you somewhere better than you are today.

What else have I been up to?

In case this is the first thing on the internet you have read in the last month, I am here to inform you that it’s cherry blossom szn.

I was up in Boston with Ben for the beautiful northeastern spring (40F and rainy), so missed the big cherry blossom runs down here in DC. But I got to do this smaller 5k in the Congressional Cemetery this weekend. I may not be getting faster, but I am getting more consistent, which is a slow (years’ long) burn to a PR. Or not! Who cares?

Tuberculosis set the standard for “cool.”

Okay, maybe not entirely. But in Everything is Tuberculosis, John Green makes the case that this tiny little “evil atom” of a bacterium has been such a persistent part of human existence that it’s shaped culture — including what’s popular.

Green notes that disease has always been about morality. We like to think that those who are sick did something (bad) to become that way, which means that it’s possible for those of us who are healthy (good) to avoid it.

This is bogus, of course, as folks in Europe in the 1800s and early 1900s came to observe. Nearly one in three deaths across all walks of life was due to TB. It was impossible to argue that all those people were of ill moral code.

Rather than admitting that the conflation of health and morality was a misstep, we humans did what we do best and dug our heels in: We simply made consumption cool. Those who were waifish and pale with rosy cheeks became admirable. They were morose creatives full of hip apathy.

My former colleague Marc Bain wrote this piece about the concept of “cool” against the backdrop of capitalism back in 2016. Cool, he argues, is “an attitude, a term of approval, and today, as much as any of these things, it’s a game of superficially rebellious status-chasing, centered on consumerism.”

What’s counterculture to thriving in the material world? Wasting away into the creative ether with a delicate cough.

There is nothing actually cool about TB. It’s a long, slow, brutal infection that leads to a painful death. And now, Green argues, the only reason it persists is because the disease exists where the cure isn’t, and vice versa.

Follow me on Storygraph for more of my recent reads.

Follow me on Instagram for the rest of my life. It’s a lot of cat content.

That’s all for now. Stay curious, friend! ❤️

If you’re new here, welcome. This newsletter came about from my health reporter days when I wanted to find a way to give life to the fascinating tidbits that got cut from my stories. Now it’s evolved into a space where I write about what I learn wherever I can.

Stumbled upon this - is it possible that I remember that collection of essays from FIS?! The cover looks familiar. I also remember thinking that you were a genius and too smart to be in a normal school. Sending big hugs x